by Mateen Khan

Delivered November 4, 2023, at AMMSA National Conference 2023, World Astoria Manor, New York City.

Summary: This paper, adapted from a keynote address delivered at the AMMSA National Conference 2023, argues for the reintegration of Islamic epistemology and metaphysics into the practice of contemporary medicine. Drawing from classical Islamic ontology, the lecture critiques the dominance of philosophical naturalism in modern medical education and clinical reasoning, which posits a closed system of causality devoid of transcendent meaning. It outlines how earlier Muslim physicians and scholars synthesized revelation, reason, and empirical inquiry within a cohesive intellectual framework rooted in tawḥīd (divine unity) and proposes that this legacy be revived and adapted for the modern Muslim practitioner.

وَإِذْ قَالَ رَبُّكَ لِلْمَلَائِكَةِ إِنِّي جَاعِلٌ فِي الْأَرْضِ خَلِيفَةً ۖ قَالُوا أَتَجْعَلُ فِيهَا مَن يُفْسِدُ فِيهَا وَيَسْفِكُ الدِّمَاءَ وَنَحْنُ نُسَبِّحُ بِحَمْدِكَ وَنُقَدِّسُ لَكَ ۖ قَالَ إِنِّي أَعْلَمُ مَا لَا تَعْلَمُونَ ﴿٣٠﴾ وَعَلَّمَ آدَمَ الْأَسْمَاءَ كُلَّهَا ثُمَّ عَرَضَهُمْ عَلَى الْمَلَائِكَةِ فَقَالَ أَنبِئُونِي بِأَسْمَاءِ هَٰؤُلَاءِ إِن كُنتُمْ صَادِقِينَ ﴿٣١﴾ قَالُوا سُبْحَانَكَ لَا عِلْمَ لَنَا إِلَّا مَا عَلَّمْتَنَا ۖ إِنَّكَ أَنتَ الْعَلِيمُ الْحَكِيمُ ﴿٣٢﴾ قَالَ يَا آدَمُ أَنبِئْهُم بِأَسْمَائِهِمْ ۖ فَلَمَّا أَنبَأَهُم بِأَسْمَائِهِمْ قَالَ أَلَمْ أَقُل لَّكُمْ إِنِّي أَعْلَمُ غَيْبَ السَّمَاوَاتِ وَالْأَرْضِ وَأَعْلَمُ مَا تُبْدُونَ وَمَا كُنتُمْ تَكْتُمُونَ ﴿٣٣﴾ وَإِذْ قُلْنَا لِلْمَلَائِكَةِ اسْجُدُوا لِآدَمَ فَسَجَدُوا إِلَّا إِبْلِيسَ أَبَىٰ وَاسْتَكْبَرَ وَكَانَ مِنَ الْكَافِرِينَ ﴿٣٤﴾

(Remember) when your Lord said to the angels, “I am going to create a deputy on the earth!” They said, “Will You create there one who will spread disorder on the earth and cause bloodshed, while we proclaim Your purity, along with your praise, and sanctify Your name?” He said, “Certainly, I know what you know not.” And He taught Adam the names, all of them; then presented them before the angels, and said, “Tell me their names, if you are right.” They said, “To You belongs all purity! We have no knowledge except what You have given us. Surely, You alone are the All-knowing, All-wise.” He said, “O Adam, tell them the names of all these.” When he told them their names, Allah said, “Did I not tell you that I know the secrets of the skies and of the earth, and that I know what you disclose and what you conceal And when We said to the angels: “Prostrate yourselves before Adam!” So, they prostrated themselves, all but Iblīs (Shayṭān). He refused, showed arrogance and became one of the infidels.

Why an Islamic Paradigm Matters in Medicine

This is going to be a somewhat heavy discussion. However, I think it’s extraordinarily important. So, I want you to listen, listen carefully. This is one of those talks where it builds. And if you miss a couple of minutes while your mind drifts off, you will miss something important.

Let me start by saying that there have been several generations of Muslim American physicians at this point. You are not the first, and I was not the first. Through the work of those who came before us—mostly immigrants—Muslims have become ubiquitous in medicine. In fact, we are overrepresented in the field. Those before us have brought tremendous value to it. But what I hope for you, what I want for you, is to move medicine in a direction that we did not—one that we haven’t been able to effectively pursue.

To take those steps, I’ll begin with a brief introduction.

Revelation and the Foundations of Knowledge

The Qur’anic verses above refer to two significant events between Allah and the angels. The first is when Allah informs the angels about the unique status of mankind. Despite our tendency toward self-harm and disobedience, Allah gave us the mantle of khalīfa—viceregent of this world. It is a weighty responsibility. Allah endowed us with the capacity to acquire knowledge and to apply it, whether in obedience or disobedience.

The second event illustrates the difference between the angels and Shayṭān. When commanded to perform sujūd (prostration), the angels acted on it without hesitation. Shayṭān, however, refused. His arrogance and denial prevented him from submitting.

As we proceed with this lecture and reflect on the rich intellectual history of Islam, keep two points in mind: the importance of acquiring knowledge and the necessity of applying it correctly. Proper application means iṭāʿa—obedience to Allah, the Exalted. This is what forms your foundation as Muslims.

Now, ask yourself: why are you here today? You are not here just because you want to be physicians—there are many other conferences for that. You are here because you are Muslims who want to pursue medicine. We cannot overlook the Islamic dimension in this equation, as it defines the purpose of our participation today. In fact, it defines the very purpose of our existence.

Let us briefly travel back to the time of the Prophet of Allah ﷺ. Arabia was a blank canvas for intellectual thought. That does not mean that the Arabs lacked intelligence, but rather that they were not bound by any rigid intellectual paradigms or ideologies. They were not beholden to the various ‘-isms’ that dominate thought today.

Into this environment, Allah sent His messengers with waḥy—divine revelation. The people absorbed it like a sponge. Whatever came from the Qur’an and Sunna was deeply internalized, and from it, they constructed a new framework for life and thought.

Let me use the metaphor of a lighthouse to describe this. They built an intellectual lighthouse, with its structure composed of the teachings of the Qur’an and the actions and statements of the Prophet ﷺ. From this Islamic lighthouse, one could look out across the world and see the different ideas, ideologies, and methodologies that exist. It stands as a beacon, guiding those who seek hidāya—divine guidance—and aspire to be not just good individuals but also competent and moral physicians. This lighthouse shows the way forward for anyone seeking to live a meaningful, principled life.

In the past, science was not what it is today. Medicine was not what it is today. We didn’t have science as a distinct field the way we understand it now—that came much later. Back then, if you wanted to understand the universe, you studied philosophy. In other words, philosophy in the past functioned as the science of the time.

What Islam did—and I’ll elaborate on this a bit more later—was engage with the existing philosophy, particularly Greco-Alexandrian philosophy. It adopted aspects of Greek philosophy but within an Islamic framework. The foundation always remained the Qur’an and the Sunna. Islam adopted these external ideas, utilized them as tools, and refined them. This process took place around the 3rd century Hijri, during a period when Islamic civilization was beginning to codify and organize knowledge. This is a crucial point that many people often overlook.

The Ṣaḥāba (companions of the Prophet) took the Qur’an and the Sunna, and, along with the salaf (the early generations), learned, propagated, and developed a framework for understanding them. It was through this framework that subsequent Muslim scientists and theologians engaged with and understood the world. That is, when new information arose, it was filtered and understood through this Islamic lens.

In a way, we can say that the Ṣaḥāba had a pure and unmediated outlook. The salaf and the scholars who followed systematized and codified that outlook, creating a structured framework that could be built upon further. This intellectual lighthouse offered Muslims a vantage point. It enabled them to take revelation and prophecy, integrate it into their worldview, and project it outward to the rest of the world.

The Rise and Decline of Integrated Islamic Thought

Islam also absorbed external ideas and reoriented them within an Islamic paradigm. Some of the earliest Muslim philosophers—though when I say philosophers, I do not mean what you might think of today—were more akin to scientists in their time. I am not referring to falsafa in the later, specialized sense but rather to those who engaged with the sciences of their era.

For example, Abū Yūsuf al-Kindī, one of the first Muslim philosophers. He was pious and knowledgeable. He studied the dīn (religion), and what he did—and what he initiated—was the integration of philosophy into an Islamic worldview, one that was bound by tawḥīd and waḥy. This aligns with what Allah says in the Qur’an:

يُؤْتِي الْحِكْمَةَ مَن يَشَاءُ ۚ وَمَن يُؤْتَ الْحِكْمَةَ فَقَدْ أُوتِيَ خَيْرًا كَثِيرًا ۗ وَمَا يَذَّكَّرُ إِلَّا أُولُو الْأَلْبَابِ

“Allah gives wisdom and knowledge to whomsoever He wills. And whoever receives wisdom has certainly been given much goodness. And none will take heed except those of intellect.” (2:269)

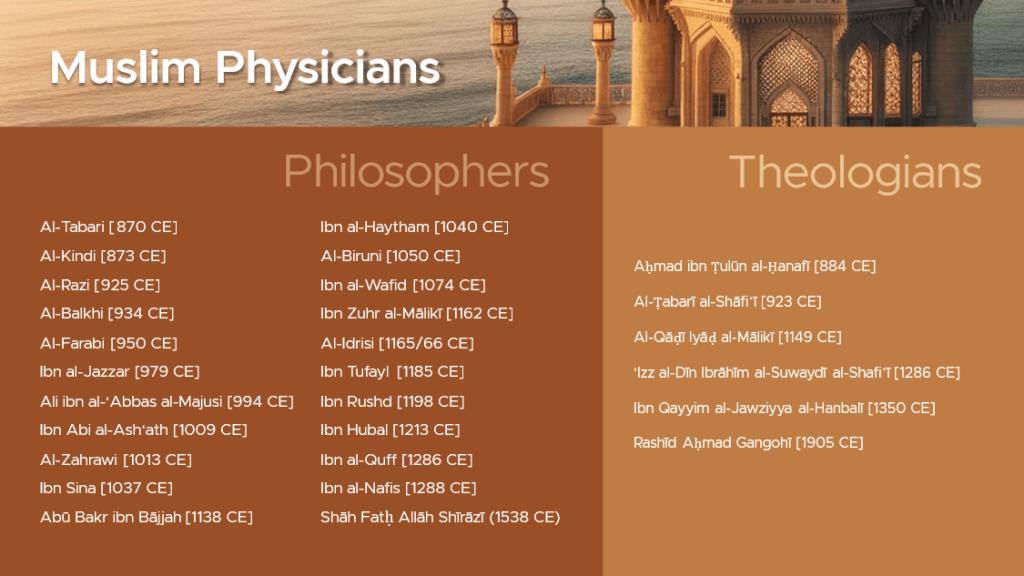

The above slide is just a brief compilation of early Muslim philosophers and theologians. Each of these figures was a physician of their time. In fact, every single one was both a physician and a scholar. But before becoming physicians, they studied the foundational tenets of Islam. They understood the Islamic framework and applied it to medicine, incorporating contemporary medical knowledge.

Why wouldn’t they do this? Why wouldn’t they integrate scientific knowledge into their Islamic worldview? After all, science seeks to understand the created world—and all of creation originates from Allah, the Creator. It follows, then, that science cannot be meaningfully separated from the greater reality: the reality of Allah and our existence as His servants. The Islamic perspective holds that Allah is not a distant architect, but One who is continuously present and actively sustaining every aspect of His creation.

For centuries, Western philosophy was essentially Muslim philosophy. The two were fused together for a time. When you look at figures like al-Fārābī and Ibn Sīnā—who were not only physicians but also remarkable intellectuals in philosophy and science—that was the science the West embraced. Now, some of these scholars had ʿaqīda issues, and I’m just pointing that out in case someone wants to raise their hand and say, “Shaykh, they had ʿaqīda issues!” Yes, they did. But the point here is not their personal beliefs. What matters is how they approached medicine as physicians, philosophers, and theologians. They understood and practiced medicine through the intellectual lens of Islam.

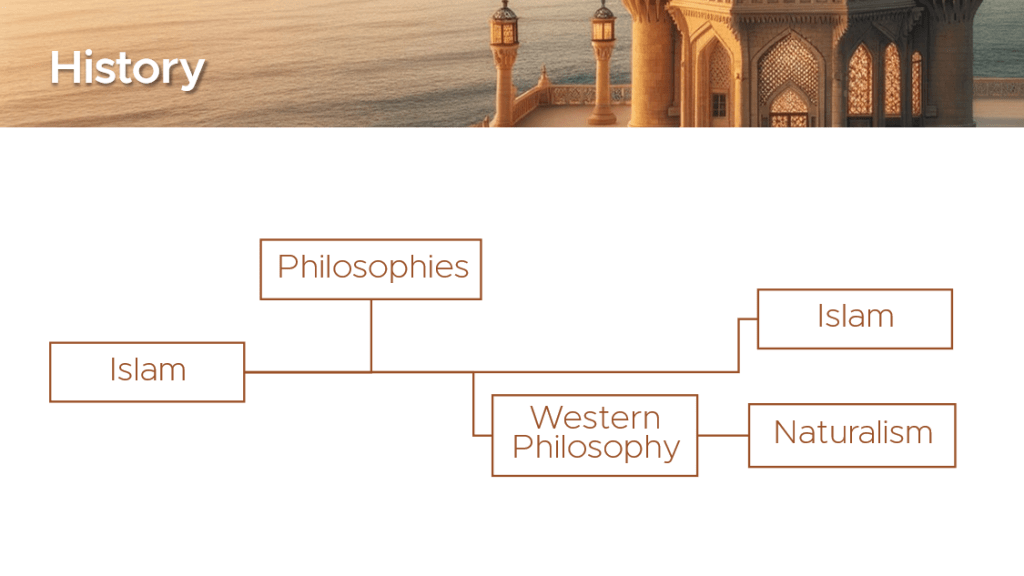

Let’s look at this slide. What Islam did was to take its framework and, as it encountered other philosophies over time, incorporated them in beneficial ways. Islam never lost its essence—what it means to be Muslim or what Islam itself signifies. Instead, it identified what was valuable in other philosophies, extracted the useful tools, integrated them subject to its framework, and made them part of its intellectual tradition.

Eventually, though, a break occurred between the two. As I mentioned earlier, Western philosophy was essentially a continuation of Muslim philosophy, and it remained unified until the time of the break. What we saw in the Muslim world during that period was the absence of any division between religion and spirituality, as well as science and philosophy. In contrast, the European tradition, after the two broke paths, took an entirely different direction. It separated out lived religion and practiced science. Islamic philosophy, however, remained rational, spiritual, and practical. That’s the essence of it—it’s grounded in reason and aimed at practical benefit.

As scientists and physicians, we did not study biology merely for the sake of understanding life; we sought to understand it as a creation. And by understanding creation, we aimed to understand the Creator. Muṣṭafā Ṣabrī, a phenomenal Ottoman scholar from the later period of the Ottoman Empire, made a profound argument. He said:

“If the religion of the Westerners had been Islam and not Christianity, there would never have been a need for the Enlightenment that occurred in Europe. And Western scholars would not oppose religion at all, as they do today.”

In other words, if you had been training as a physician during that period, you would have practiced medicine through the lens of Islam. What does it mean to practice medicine through the lens of Islam? I’ll get to that.

Around the 13th century, a split occurred. A great Muslim scholar, philosopher, and Mālikī jurist named Ibn Rushd, who was also a physician, addressed this issue directly. He argued that what the dīn said and the information provided by modern science should not be contradictory. A single mind should be able to encompass both: a physician and a Muslim, leading to a complete human being.

Ibn Rushd did not introduce something new; instead, he maintained the unity between Islam and science. He upheld the principle that the two belong together. Other scholars, like Abū Ḥāmid al-Ghazālī and Muṣṭafā Ṣabrī, continued this tradition, and it has persisted as long as this framework has endured—and, to some extent, still does today.

However, Western philosophy took a different trajectory from Ibn Rushd’s teachings than that of the Muslims. The details of this are beyond the scope of my talk, but essentially, the Western intellectual tradition branched off into secularism. In doing so, it stripped medicine of its spirit—of its rūḥ. Medicine lost its connection to religion, divine revelation, and objective morality, and what remained was purely rational and subjective reasoning. In other words, it was science, but it lost its soul.

Meanwhile, the Muslim world stayed on its original trajectory, preserving the integration of science and spirituality, until about the 19th century. At that point, under the influence of modernism spreading across the globe, Muslim physicians began to abandon this integration. We started to practice medicine in the same secularized manner that had taken hold in the West.

This is where we are now. This is where I found myself, and where most Muslim physicians in the United States find themselves today. What I want to draw your attention to is this: As Muslim physicians—and I’m not just talking about you, but also myself and those who came before me—we have been Muslims practicing medicine in the United States. However, we checked our Islam at the door when we entered the field. And the truth is, we never had to do that.

You saw the list of scholars earlier, and that was just the list I happened to find. There are many others, including those who were not as famous. The physician of their time was deeply rooted in both Islam and medicine, as a normal course of their practice.

Philosophical Naturalism and Its Consequences

Carl Sagan—you may not be familiar with him, though some of you might have heard the name—was a well-known scientist. He had a famous television show called Cosmos that aired in 1980, long before any of you were born, I’m sure. In that show, he made the statement: “The cosmos is all that is, or ever was, or ever will be.”

Now, this is not a statement of fact—it’s a statement of belief. By “cosmos,” he means the universe. What Sagan is saying is that nothing exists beyond what we can observe—physical matter and energy. This statement reflects a philosophical framework, not an objective truth. Essentially, Sagan proposes that the only things that exist are those that we can see, measure, or quantify.

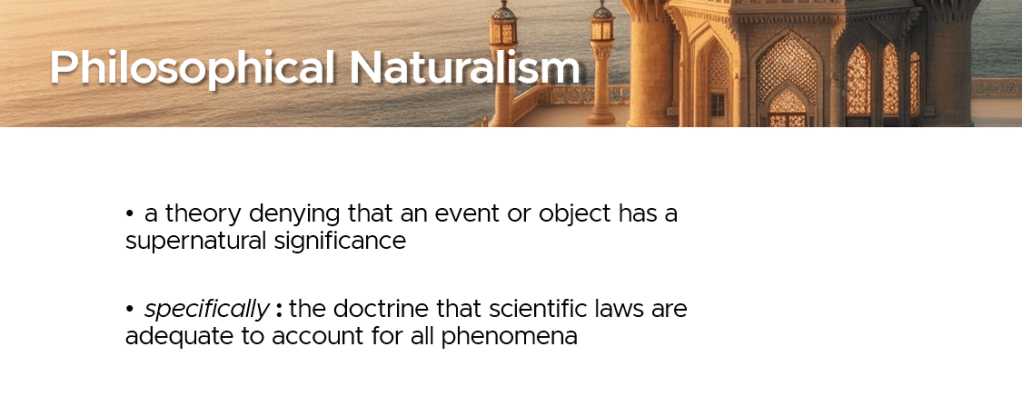

Medicine today is built on the same philosophical framework that Sagan promoted. This framework is called philosophical naturalism. You might also hear it referred to as materialism, empiricism, or similar terms, but for today, I will use the term philosophical naturalism.

For a naturalist, the universe is a closed system of cause and effect. It consists solely of atoms and matter, with no higher purpose or meaning. For example, in this view, pain is nothing more than neurons firing in the brain. Death is simply the cessation of that firing—nothing more. Although we might assign value or meaning to life, according to this framework, any value we assign is arbitrary and without inherent meaning.

So, philosophical naturalism is a theory that denies any supernatural significance to events or objects. In other words, it is the doctrine that scientific laws are sufficient to account for all phenomena—there is nothing beyond or outside of them. This philosophy dominates modern medicine and science today.

As I mentioned, we do not have to accept this framework.

Richard Dawkins—many of you have probably heard of him—is a well-known atheist. He once said:

“On the contrary, if the universe were just electrons and selfish genes, meaningless tragedies like the crashing of a bus are exactly what we should expect, along with equally meaningless good fortune. Such a universe would be neither evil nor good in intention; it would manifest no intentions of any kind in a universe of blind physical forces and genetic replication. Some people are going to get hurt; others are going to get lucky, and you won’t find any rhyme or reason in it, nor any justice.”

In other words, naturalism claims that life has no inherent purpose. There is nothing beyond the material system—no belief in higher existence or divine intervention. Even when naturalism leads to absurd conclusions—such as the idea that the entire universe came from nothing, without any cause —a naturalist is still committed to that belief. That is because their philosophy presupposes that only material causes and explanations exist.

Islam categorically rejects this notion. Islam says this is all nonsense.

There is a glaring contradiction here, one that affects all of us—those before me, myself, and you. What is this contradiction? Despite the large number of Muslims in medicine today, most of us operate within the framework of naturalism, at least while we are at work or school. As a result, many of us experience cognitive dissonance, maintaining one mind in the medical field and another outside of it.

Rājaʾ Bahlūl, a well-known contemporary philosopher, highlighted this problem. He implies that Muslims like us are to act as if religion does not matter in the way we relate to other citizens. “But what kind of self is that, which can consistently switch between two identities? At one moment, thinking that religious beliefs and values are the most important things in life, and the next moment, acting as if they do not matter?”

Naturalism today leaves us with the belief that there is no framework for discovering truth beyond itself. It relegates religion to the private sphere, requiring us to operate in two distinct domains. It tells us to keep medicine and science secularized: one mind for faith, another for science.

Islam has always rejected this duality. There is no reason to live this way. There is no reason to think like this. We are not without precedent. If we look at our predecessors, they did not discard science; they embraced it. Islam incorporated science, rectified it, and advanced it.

The real focus of my talk is this: How do we return to that integrated approach?

As I mentioned earlier, Ibn Rushd championed this effort, continuing the process of integrating science and Islam. Scholars like al-Ghazālī and Muṣṭafā Ṣabrī did the same.

So, how is the Islamic model different from naturalism?

Islam’s Epistemology: Knowing Beyond the Empirical

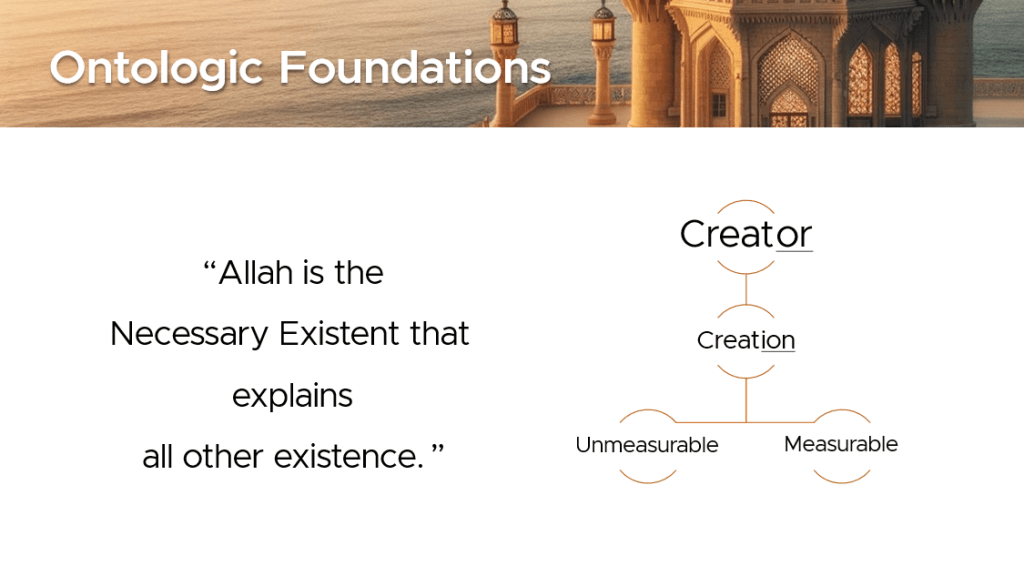

The first concept is something called ontology. It’s a philosophical term—you don’t need to know in detail. Essentially, ontology deals with what exists in reality. We’ve already seen what Carl Sagan and naturalists claim: that only the universe exists, just hard, cold atoms and nothing more.

Islam, however, presents a different ontology: Allah is the necessary existence that explains all other existence. Where Western philosophy might say, “I think, therefore I am,” Islam says, “I am, therefore Allah exists.”

Therefore, our ontology is based on this model: there is a Creator and creation. Within creation, some things are measurable, and some are not. The unmeasurable aspects include morality, ethics, purpose—questions like, What is right? What is wrong? What are we here for? Islam speaks to these matters. Concepts like duʿā, baraka, and others fall within this realm. And these things are no less real simply because they are not measurable.

This is heavy stuff, right? You probably didn’t expect a philosophy talk today, but here we are. I don’t expect you to grasp all the nuances immediately, as that requires thought. My goal is simply to bring to your attention what you’re missing. I never received this kind of discussion in med school. I didn’t get it in residency either—I had to learn it in the madrasa. You might not get that chance, which is why I’m sharing it with you now.

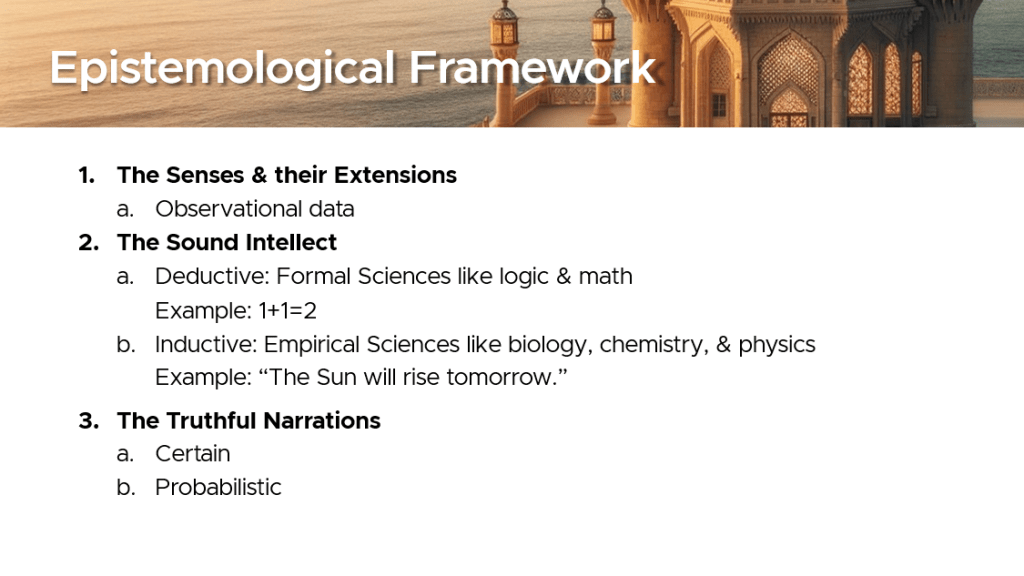

Now, this slide might be a bit difficult to read, so I’ll read it out for you. The scholars of Islam developed a tripartite approach to knowledge. Allah the Exalted says in the Qur’an:

وَاللَّهُ أَخْرَجَكُم مِّن بُطُونِ أُمَّهَاتِكُمْ لَا تَعْلَمُونَ شَيْئًا وَجَعَلَ لَكُمُ السَّمْعَ وَالْأَبْصَارَ وَالْأَفْئِدَةَ ۙ لَعَلَّكُمْ تَشْكُرُونَ

Allah brought you out from the wombs of your mothers while you knew nothing and He gave you hearing, sight, and intellect so that you might be grateful. (16:78)

What’s meant by “hearing” here is information, things people tell you. Thus, there are only three ways that you can know something. Just three.

Through direct sensory experience.

You know something because you’ve seen it or experienced it with your own five senses. For example, everything in this room—I know exists because I can see it, feel it, and experience it myself. That’s one source of knowledge: the five senses.

Through deduction or reasoning.

The second way you know things is through the intellect, by making deductions. For example, I can’t see what’s on the other side of that wall, but I know people are there. They didn’t just disappear when I walked into this room. So, deduction is another form of knowledge.

Through being told by others.

The third way we know things is through information—because we were told about it. Now, let me ask you: How many of you have been to North Korea? How many of you have met someone from North Korea? Maybe a few of you, but for most of us, we believe North Korea exists simply because we’ve been told it does. We’ve read it in books, seen it on the news, or watched videos of its leader. However, you have not personally verified its existence.

How many of you have a mother? All of you, right? Now, how many of you were there when you were born? All of you, obviously, but you don’t remember it. So, how do you know she’s really your mother? Because your father told you? But what if he lied? What if your mother lied? What if your grandparents lied? Yet, most of you probably never questioned whether she is truly your mother. Maybe a few of you have thought about it at some point, but for the most part, you accept that information without question.

Now, let me be clear: I’m not suggesting she’s not your mother. Of course, she is. What I am trying to show you is that we often rely on information provided by others for much of what we believe. And that’s perfectly fine, that’s how we function as human beings. There’s no reason to doubt all that information.

One of you in the room might raise their hand and say, “Oh, I could get a DNA test.” Will you run the test yourself? And when you receive a letter confirming she’s your mother, why would you trust the letter? That’s still just more information from someone else, right? It’s the same thing: someone else telling you, “Yes, she’s your mom.” But you don’t know for sure because you’re relying on others for that knowledge.

So, the point is, there is knowledge that we accept simply because we were told it—and that’s perfectly legitimate.

Allah the Exalted says in the Qur’an,

وَلَا تَقْفُ مَا لَيْسَ لَكَ بِهِ عِلْمٌ ۚ إِنَّ السَّمْعَ وَالْبَصَرَ وَالْفُؤَادَ كُلُّ أُولَٰئِكَ كَانَ عَنْهُ مَسْئُولًا

Do not pursue that of which you have no knowledge. (17:36)

This means that knowledge comes through the five senses, through information passed to you, and through your intellect. Allah adds that you will be asked about these forms of knowledge. In other words, you are responsible for what you learn and how you use the knowledge gained through your senses, your reasoning, and the information shared with you.

This framework establishes a model for gaining knowledge that scholars have followed throughout Islamic history. In past times, as a Muslim, you would have learned this before studying medicine. Knowledge comes from several sources, starting with the five senses and their extensions—such as microscopes, telescopes, and other tools. This is empirical evidence, or observation.

Many of you are presenting research posters downstairs, and this is precisely what you did: gather data through observation. However, despite the immense benefits of empirical evidence, it is still limited. As I mentioned earlier, I can’t see what’s beyond the door, and there are other things that my five senses alone cannot tell me. How do I process the information I have? I need to deduce and induce conclusions from it, and for that, I need the intellect.

The intellect fills the gaps where sensory data cannot. Now, let’s briefly explore the two types of intellect: deductive and inductive reasoning.

- Deductive Reasoning

Deductive reasoning gives us conclusions that are logically certain. For example, 1 + 1 = 2. Any doubt about that? Of course not. This branch of intellect covers logic and mathematics—fields in which we achieve 100% certainty. We don’t doubt logical truths, such as “there cannot be a married bachelor.” These are universally accepted facts.

- Inductive Reasoning

Inductive reasoning, on the other hand, involves drawing conclusions based on observation and experience. This is the foundation of empirical sciences. For instance, consider the statement, “The sun will rise tomorrow.” How many of us doubt that? None of us, because the sun has risen every day for billions of years. But here’s the question: does it have to rise tomorrow? Is it as certain as 1 + 1 = 2? Not exactly. Inductive reasoning may yield conclusions that are highly probable but not absolutely certain.

All of biology, chemistry, physics, and medicine rely on this type of reasoning. It’s how we make predictions and act upon them, even though they are not guaranteed with absolute certainty. I would like you to consider this distinction later. For now, I just want you to grasp the framework. The details—the things that might seem overwhelming—you can process later or ask about during the Q&A.

This brings us to the final type of knowledge: revelation (Qur’an and Sunna), also known as narrations. The intellect, while powerful, is also limited. It can tell us that we exist, but it cannot tell us why we exist. It doesn’t provide answers about our purpose or what we should do during our time here. For these objective truths, we need another source: revelation.

This is similar to the earlier example I gave about North Korea—you believe it exists because you were told it does. Revelation works in the same way. This category includes everything the Prophet ﷺ conveyed to us from the Qur’an and Sunna—all of it is waḥī from Allah. It was narrated to us by the Prophet ﷺ, and through it, we come to know with certainty that:

- There is a Creator.

- This Creator made us and placed us on this planet as His khalīfa.

- We have responsibilities in this world, and Allah will question us about them.

- The Prophet ﷺ was sent as a messenger to guide us.

Once we know these truths, the question becomes: How do we integrate them with everything else we know? This process of aligning all the different sources of knowledge and making sense of them is what we call epistemology. It’s about harmonizing everything you know into a coherent worldview, one that shapes who you are.

This is why the Muslim intelligentsia thinks differently from their non-Muslim counterparts. They view the world through the lens of revelation, standing from the vantage point of that lighthouse we spoke about earlier. This perspective enables them to integrate empirical knowledge with the divine truths revealed through the Qur’an and Sunna, thereby creating a comprehensive and unified worldview.

This presents a significant challenge for us today, and it’s the challenge I wanted to bring to you: if you want to contribute to medicine in the most meaningful way, you need to learn the foundations and rulings of Islam. Now, I’m not saying you have to become an ʿālim (scholar), but you should at least be familiar with the Islamic paradigm. You need to understand where you fit within that framework, so you can place your practice in its proper context.

The worldview I’ve been discussing is akin to a computer’s code. A computer by itself is just hardware – chips and circuits – but it needs programming to function properly. When the computer receives input, it knows how to process it according to its code. Islam is our programming. When we receive knowledge from any of the sources I mentioned earlier, whether through observation, intellect, or revelation, we need to process it in alignment with the framework that Allah has given us.

Islam is not just about praying five times a day. It’s not just fasting in Ramadan or having a Muslim identity. Islam is much more than that. It is unlike some other religions, where you practice only on a certain day or only when you’re at home. Islam is a complete way of life. It provides not only guidelines but also teaches you how to think about and approach the world around you.

Practical Guidance: Living Your Faith in Medicine

Let’s now consider some practical implications. Earlier, we discussed ontology and epistemology, which form the framework by which we engage with reality. Allah created this reality. Prophets were sent with messages, and we are meant to learn, absorb, and adapt those teachings into our lives. Now, with this framework in mind, we look out at the world, and that perspective must influence how we interact with it.

For example, the Islamic framework can guide us on significant questions:

- What should we do at the beginning of life?

- What should we do at the end of life?

- What are the rulings regarding organ transplantation or the creation of synthetic organs?

- Which medications and vaccines are permissible? Which procedures might be impermissible?

We can learn all of this from Islamic teachings. For instance, some medications contain ḥarām (forbidden) ingredients, such as porcine enzymes. Is it permissible to use them? If so, under what conditions? Why would it be permissible to inject something we are not allowed to consume orally? When we encounter modern issues, such as permissible medications or vaccines, we need to think deeply about them, not just accept or reject them blindly.

There are also challenges associated with caring for individuals with alternative lifestyles. How do we navigate these situations as Muslims? The goal isn’t to approach it with blinders on. For instance, it’s not about saying, “Oh, you’re LGBT—so I’m just going to pretend you’re not.” That’s not the way forward.

The real question is: How can we care for people in a way that is most beneficial to them while also protecting everyone else, including ourselves? This requires wisdom and a balanced approach – an Islamic approach.

Similarly, issues like euthanasia, whether passive or active, also need to be addressed thoughtfully. Should we keep someone alive at all costs, or are there circumstances when ending life support is permissible? These are not questions that naturalism can answer. It simply cannot provide the guidance we need for such complex, moral questions.

There are other issues as well, such as the boundaries between genders. Can we make our gatherings better? There is no question that gender segregation is part of our dīn. If someone wants to argue otherwise, we need to ask: Are they saying that based on the conclusions of Islam, or are they influenced by an external philosophy?

The point is the fiqhī (jurisprudential) aspects of how we gather and interact. Gender segregation is undeniably part of Islam. So, when Muslims come together, if we want to do so in the best way, the way that will earn the pleasure of Allah, then our interactions should align with that framework.

I’m actually happy with how things are organized here today. It’s better than I expected. I’m not trying to put anyone down, but it’s good to see that, for the most part, the women are on one side, and the men are on the other. We must keep this in mind when we apply our values to medicine. Not because we want to force anything on others, but because we truly believe that what Islam teaches is the best way.

It’s not just beneficial for us; it’s beneficial for everyone. We don’t need to force people, but we can guide them. We can explain to them the wisdom of our way, and we can remain within that framework. This is who we are.

Now, there are many other issues today, and even more will arise in the future. You will have to grapple with them. If you don’t understand the Islamic paradigm, you won’t know how to respond, and you’ll end up defaulting to ethical frameworks that are not ours. You’ll rely on journals or guidelines based on naturalism. Why does this happen? Because we never took the time to learn what our own “-ism” is. We never bothered to understand the framework that Islam provides.

As a result, we often default to what we were taught in medical school or imitate what our colleagues are doing. But we can do better. This is what my generation and the generation before us missed. We were Muslims in medicine, but we didn’t bring Islam into medicine.

I want you to go one step further. I want you to bring Islam into medicine. You can do better than we did.

Reclaiming Our Intellectual Tradition

There are many benefits to adopting an Islamic paradigm in medicine.

- Unified Thinking Across All Aspects of Life

As we discussed earlier, you don’t need to compartmentalize your thinking. You don’t have to be, for lack of a better term, split-personality: where you think and act one way at home or in the masjid and another way in the hospital. You don’t need to live with this split mindset. Islam provides a framework that unites every part of your life.

- A Whole Practitioner

When you have confidence in your spirituality, thought processes, and framework, you become a well-rounded practitioner. You won’t experience the same kind of burnout that comes from constantly shifting between different identities. When you’re grounded in one cohesive system, you’re more resilient.

- Extending Benefits to Everyone

This paradigm extends benefits not just to yourself and Muslim patients but to everyone. You serve humanity, as Islam teaches, by looking after the welfare of all individuals, regardless of their faith.

- Treating the Whole Human Being

Islam teaches us to treat the person, not just a collection of atoms. There was a time in medicine, maybe before your time but still within mine, when it was purely biological. Medicine was taught as anatomy, physiology, and biochemistry, with little concern for the psychological or spiritual aspects of health. You were essentially viewed as a biological machine, and treatment was focused on fixing that machine.

Medicine suffered from this mindset because it was built on philosophical naturalism, which had no accommodation for the non-physical aspects of the human being. Eventually, people realized that treating patients as mere biological systems was insufficient, and now you’re probably learning about the importance of spirituality, psychology, and well-being in healthcare. But even now, these ideas are often awkwardly integrated, as if being forced into a system that wasn’t designed to accommodate them.

Islam, however, has always viewed the human being holistically, as both body and soul. Every human being is a creation of Allah, just like you are. Allah loves them just as He loves you. That is how you should approach patient care: with this understanding.

- A More Moral Practice of Medicine

The Islamic framework provides clear guidance on why we practice medicine and how we should do it in the best way. It introduces morality into the practice, ensuring that the work is done with intention and purpose.

- An Uplifting Influence for Other Theological Perspectives

Adopting this paradigm is not only beneficial for Muslims, but it can also uplift other theological perspectives. Islam teaches us in the Qur’an,

وَلَا تَكُونُوا كَالَّذِينَ نَسُوا اللَّهَ فَأَنسَاهُمْ أَنفُسَهُمْ ۚ أُولَٰئِكَ هُمُ الْفَاسِقُونَ

Do not be like those who forgot Allah, so He caused them to forget their own selves. (59:19)

This verse reminds us that when people forget Allah’s message and the framework He gave us, they also lose sight of themselves. That is exactly what happened in medicine: people forgot the human being in their obsession with treating biology. The Qur’an continues, “It is they who are the corrupt.”

And we’ve seen this happen; we still see it today. When people forget Allah, they forget morality, purpose, and the wholeness of the human being. This neglect can lead to corruption, even within the medical field.

There are some challenges we need to face to reintroduce this paradigm and bring it back into medicine.

- Education

The first challenge is education, specifically educating Muslim medical students. As for people like me and those older than me, we’re mostly set in our ways. I’ve tried to change people, and they’re very resistant. However, you are still being molded. What you learn in med school will stay with you for the rest of your life. I’m 20 years out of med school, and I still carry everything I learned back then. You will, too. So, this is the time to educate yourself in these areas.

- Foundations of the Dīn (Uṣūl al-Dīn)

This includes topics like ontology and epistemology, the fundamental concepts we’ve discussed earlier.

- Fiqh Essentials (Farḍ al-ʿAyn)

These are the essential rulings that every Muslim individual needs to know to live their faith. These include personal practices like ṣalāh, fasting, and dietary laws.

- Farḍ al-Kifāyah for Physicians

As a physician, you also need to know what the farḍ al-kifāyah entails. This includes the Islamic rulings necessary to take care of people properly, such as issues related to end-of-life care, organ transplantation, and permissible treatments.

- Tazkiyah and Iḥsān (Self-Development)

This involves the techniques of self-purification and striving for excellence. If you become a better person, you’ll be a better physician. If you become a better Muslim, you’ll be a better physician.

At this point, I could go on for another hour about the importance of demanding tolerance for the Islamic paradigm and its conclusions. For a long time, we’ve had to hide our Islam. Sure, we might say salām, some of us wear beards or hijābs, but in our thinking and interactions, we act no different from others.

Right now, the field, particularly science, is closed to the idea that there can be another paradigm. The dominant framework today is philosophical naturalism. I’ve explained it to you, along with its limitations. But why should we accept a lack of diversity in thought (i.e., paradigms)?

In medicine, we celebrate the diversity of people. We have diversity in ethnicities and backgrounds, but we lack real diversity in foundational thought. Why can’t we? Why can’t we have practitioners with different philosophical perspectives? You might say, “You’re a philosophical naturalist, so you practice this way and draw these conclusions. I’m a Muslim, so I think this way, practice this way, and come to different conclusions.” We don’t need to fight over it. We can coexist with these differences.

You’ve probably noticed during your rotations that different physicians have different practices. There are multiple approaches within medicine. So, why can’t we reintroduce the Islamic outlook, the same outlook that once benefited people?

Medicine today is often seen as areligion, meaning without religion, but that’s not true. It does have a philosophical framework, and that framework serves as a de facto religion. Are you following me? I’m not going too philosophical, am I? Good.

So, medicine does have a de facto religion, and that religion is philosophical naturalism. It dictates what you believe, what exists, and how to process information. Islam does all of that too. And their philosophical framework, their de facto religion, is not inherently better than ours. There’s no objective reason why our paradigm should be excluded from the conversation.

A Way Forward for Muslim Physicians

Some closing thoughts: Islam is a comprehensive framework. It encompasses everything. It not only tells you how things happen but also why they happen and for what purpose. The acquisition of ʿilm (knowledge) and its best application, meaning doing what is right, is the heritage and duty of every Muslim in medicine.

Our predecessors had a comprehensive ontology and epistemology rooted in an Islamic worldview. But we, as Muslims in the West, have put on blinders. When we practice medicine, we view it solely through the lens of modern frameworks, leaving Islam on the periphery. We don’t have to be like that. Muslims have the potential to serve as a moral compass in medicine, and that is what has brought all of us together today.

Morality, knowing what is right and wrong, is divinely instructed to us. Islam provides guidance for what is best for humanity, even in the field of medicine.

Allah has no personal need for your prayers, fasting, or adherence to ḥalāl and avoidance of ḥarām. Whether we follow these commandments or ignore them, it does not benefit or harm Him in the least. It is all for our own benefit. I’m not just talking about ʿibādah (acts of worship) but about every command, prohibition, insight, and framework within Islam: it all exists for the benefit of mankind as a whole.

If we keep this knowledge to ourselves or fail to learn it, we are leaving behind the khayran kathīran (great good) that Allah has promised. Worse, we are denying our patients the benefit of that good.

Now, I know that what I’m suggesting today is ambitious. Some of you may be thinking, “This isn’t realistic. Be practical.” But what I’m calling for is a type of renaissance: a new way of looking at medicine. It requires a renewed, active deconstruction of the thought processes we have been trained in, starting with the frameworks you learned in undergrad and medical school.

I am not saying to abandon science. We don’t need to. You’ve already seen how the Islamic framework can integrate with science. We can also view science differently, from an Islamic perspective.

We need to educate ourselves on the intellectual side of Islam. We need to push back against the grain and reject the idea that we must practice medicine according to someone else’s philosophy. We have our own framework, and we believe it to be objectively better. That is our conviction, and it’s time we put it into practice.

This is our heritage as Muslims, and we owe it to both our patients and society to give them the best that Islam offers.

It’s a lot of work, no doubt. But we can start. In shā’ Allah.

Jazākum Allāhu khayran.